Yes

folks, I was there: back in those days when zander in their millions,

blackened the surface of the Great Ouse Relief Channel, dragging hapless

seagulls to their doom and shredding them into a gloop of blood and feathers.

When a matchman hooked a bream, he was lucky if there was anything left

other than a head and backbone by the time it reached the net. This is

the true and unexpurgated story of the unstoppable rise of the zander

- the facts that THEY would rather have kept under lock and key.

This

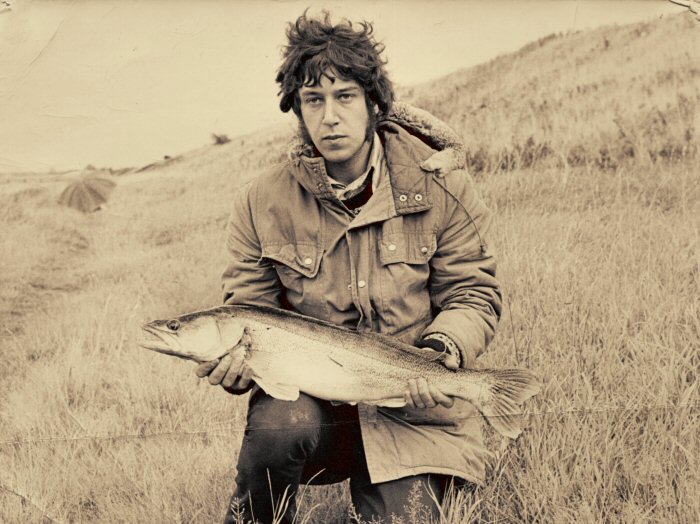

period piece is set in the dark days of the late Sixties and the early

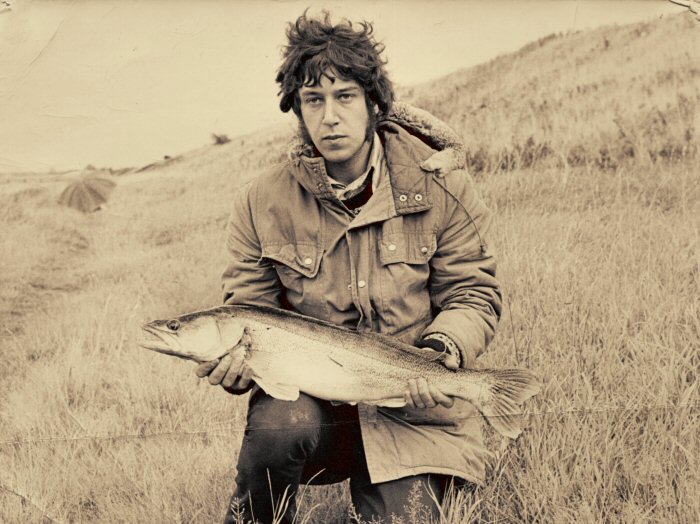

Seventies. My tangled hair and comedy sideburns must have seemed fashion

statements at the time, but now exist only on yellowing, dog-eared photographs

which pop up to embarrass me when I'm least expecting it. As whimsical

psychedelia bowed out to stern prog-rock, I had somehow managed to bluff

my way into the sixth form and the weekend trips into the Fens after predators

were a cathartic necessity. This was mainly to clear my head of such ponderous

irrelevancies as the Schleswig-Holstein question, but justified to my

parents as a means of purging myself with fresh air and healthy exercise.

The fact that these trips often left me cold-ridden and exhausted was

brushed aside as mere coincidence.

Trouble was brewing in the windswept flatlands. A well-intentioned River

Board employee had decided to introduce an exotic import to the supposedly

enclosed Great Ouse Relief Channel. Just ninety-seven zander,

or pike-perch as they were called then, were secretly introduced to the

twelve mile, fish-filled water. Just a few years later, I read an intriguing

article in the long defunct Fishing magazine entitled, "And then

they came - pike-perch from a Fenland drain". The writer and his

friends had been troubled by countless missed runs on livebaits, until

as an experiment, they scaled right down. Suddenly they were catching

one pound zander one after the other and the secret was out.

Within ten years, they had spread to such an extent that they were biting

chunks from the living flesh of large bream, stripping them down to the

bone and eating them alive like starving pirhana. By night they would

leave the water, fanning out across the fields, raping the local wildlife

and setting fire to workmen's cottages. Panic spread throughout the kingdom

from Mildenhall to Kings Lynn. A hired killer was brought in. His name

was Bear - George Bear. Many a captured zander was nailed to the village

cross or burned alive in a wicker cage. Norfolk was awash with blood and

scales. In spite of all these efforts, by 1985, not a single non-predatory

fish was to be found alive in the whole of Fenland. The zander populations

were magically sustained however, as they evolved to subsist on rats and

sugar beet, with the occasional treat of a passing cyclist.

The idea of fishing for these hard-as-nails invaders was incredibly exciting

to me in my late teens. Not for me the lady-like roach or the foppish

bream. Even the pike seemed to have a rather lazy air about them, only

savouring ultra violence in short, rapid bursts. With their rough scales

and spiky dorsals these were true punks, almost ten years ahead of their

time. They didn't just grab a fish and swallow it; they would first beat

it to death with bike chains, then tear it apart, fin by fin.

A day at the Relief Channel wasn't a simple one day jaunt into the East

Anglian countryside, it required sufficient live and deadbaits to supply

a combined battery of at least twenty five rods, which were spread out

between the gaps in the reed beds over a distance of about two hundred

yards. Any old rod was pressed into service to achieve the necessary coverage,

from sawn off match rods, to six foot solid fibreglass boat rods with

rings held on by insulating tape.

The

whole day was spent speed jogging backwards and forwards along the serried

ranks of rods, hoping that the odds were in favour of arriving at a rod

as the run was just starting to develop. On days when the pike and zander

were particularly un-co-operative, we must have covered twenty to thirty

miles each, over soggy ground and without stopping. Very impressive when

you consider that this was all carried out in knitted balaclavas, snorkel

parkas and wellies.

The

Saturday morning livebait catching sessions were often marathon efforts,

requiring an amount of dedication that would be unthinkable for any sensible

person once past the madness of their late teens. Friday nights were reserved

for searching out whichever watering holes served the now legendary Ruddles

County. Now let me make a distinction here: Ruddles County in those days

was a fierce and potent brew made from discarded engine oil and strained

through doormats. It bore not even a passing resemblance to the bland,

commercial fizz that has been passed off under its name in more recent

times.

To a seventeen year old, a pint of County was something to be feared.

It was intended to be served completely flat and most definitely contained

girders. Anyone being served a pint of County with a head on it would

probably complain to the landlord that it was off. Its fearsome effect

on the palate can sometimes be conjured up amidst swirling clouds of nostalgia,

and with vast amounts of concentration, but one thing was for sure, it

was certainly not a girl's drink, and reserved for the most serious of

imbibers.

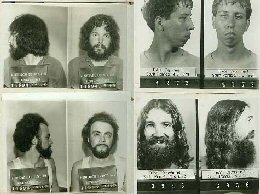

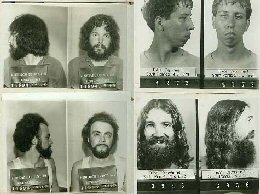

Graham

was a member of the Peterborough Specimen Group, seemingly a social club

for psychopaths, rapists and murderers, so sometimes on a Friday night,

I was given the dubious treat of a night out in their company. Although

I felt quite comfortable in the comparitively friendly Bourne boozers,

the Peterborough drinking holes were in a different league altogether.

The PSG of course, favoured the most run-down, seedy, dangerous and violent

of these. With much trepidation I edged my way past the inevitable fight

taking place in the car park of a daunting looking brick erection in the

aptly named Dogsthorpe.

I

crunched over the broken glass, and edged into the blazing interior, lit

by fluorescent strip lights, dulled only by the swirling banks of choking

smoke from the ubiquitous Player's No.6. I would stand there nervously

clutching my pint, surrounded by Graham, Big Lol, Mutley, Pete Harvey,

Chalky White, Mick Hennesey and Dennis Smith.

Mick

and Dennis seemed comparitively civilised, having obviously attended one

of the posher schools, and had quite possibly had their hair cut at some

point during the last ten years. They must have been really hard though

because they looked as if they washed and even shaved, and that was a

sure way to earn youself a beating in one of these establishments.

This

was back in the days when the breathalyser was virtually unheard of, so

on leaving the pub, I would have to wait for Graham to be sick in the

car park before driving us home. This was a talent I had yet to acquire,

and I would often be dragged out the next morning, deathly white, shivering,

and likely to scatter my stomach contents all over the countryside.

The amount of baits required caused us quite a few problems. Whole Saturdays

would be spent roaming vast distances across the Lincolnshire countryside

in an effort to collect them. If the favourite river locations failed

to produce the goods, there were a few highly illegal yet prolific venues

to fall back on. These often required a lightning dash through a hole

in a hedge and a worrying run across open ground, until refuge was gained

among the lakeside undergrowth.

The baits acquired in this way were usually rudd, which though less than

ideal would often save the day. In the beginning, all the baits would

be stored in a brewing bucket and kept alive with a battery powered pump.

Later on we became more ambitious, and bought a plastic laundry basket

specially for the purpose, which we would sunk and concealed in the deep

margins of one of the local pits; strictly private pits of course.

The first stop on the bait round would often be the Electricity Cut at

Peterborough, where you were guaranteed to catch as many bleak as you

could possibly use, although these were usually quite small, even for

bleak, and considered for emergency use only. We would stand in the bitter

cold with the evil black mud working its way up our legs, and the foul,

sickly stench of the sugar beet factory assaulting our nostrils. Sometimes

if the turbines were running, the float would disappear from view within

seconds as it was carried off into the swirling mist that always hung

over the oily, warm water. On a good day, you might catch roach or skimmer

bream, but more often than not, the bleak would grab any bait before it

even had chance to break through the surface film.

There was a sort of bait hierarchy, with chub comfortably at the top.

Roach came a close second, followed by the surface swimming dace and rudd.

Below those came the species used in sheer desperation: skimmer bream,

visible but fragile; perch, active but dull and spiky; gudgeon, game but

too small, and bleak were just too delicate, but right at the very bottom

of the pile came the poor old ruffe. If only we had known about the effectiveness

of eel sections, we would never have been without effective baits, as

all the local river, drains and even ditches absolutely swarmed with them.

The most prized baits of all were chub of around four or five ounces,

but when fishing for these, it was amazing how often we would be frustrated

by the attentions of one pound roach and three pound chub, which even

we declined to use. Saturday bait snatching expeditions were planned like

a commando raid, with first, second and third choice locations spanning

vast distances across the Fens. The round trip always ended at the private

roadside pits, which being on next morning's route, enabled a convenient

pick-up point in the darkness of the early morning.

With

any luck, we would reach our required target by dusk, giving us the necessary

cover under which to hide the laundry basket full of our plundered victims.

We had used keepnets for this purpose in the past, but these would often

come under attack from eels, even in the iciest weather, leaving us with

a high percentage of headless corpses. I now look back on our actions

under the burden of a guilty conscience, although we scarcely considered

the morality of our deeds, and even considered it quite an exciting adventure

in its own right.

We

always treated pike and zander with the utmost respect, but their rotting

corpses were a regular sight on the banks of any match lengths. Matchmen

would look into our livebait buckets with disgust, while we would look

on in horror as they tipped their nets of fish into the wire basket at

the weigh-in. It was always a good idea to be present at the end of a

match, because we were guaranteed to find a good supply of dead or dying

fish to supplement the bait supplies for the following week. As they say,

"the past is a foreign country" – different time, different

rules.

In the early days, I would go to bed at nine in the evening, ready for

when my alarm went off at 3.30am. Even in my pre-pub days, these early

starts were always difficult, as the excitement would often make it difficult

to get to sleep, and I knew that the drift into oblivion would be terminated

by the terror of something that has left mental scars to this very day.

The alarm clock I used must have been heard two streets away, and I slept

primed to leap into action within milliseconds in a futile attempt to

silence it before it woke up my long suffering parents.

The first thing I had to do on creeping downstairs was to phone Graham's

number, and let it ring just once before putting the phone down. Hopefully,

I would get the single ring in return a few seconds later to confirm that

he was out of bed, and would be around to pick me up within about half

an hour.

I can still remember quite vividly, stepping outside the back door to

sniff the morning air and assess the weather prospects. Sometimes it would

be quite atrocious, but because we had invested so much effort, we would

go absolutely regardless of conditions. I would sit out by the garden

gate in the pitch darkness waiting for the headlights to appear at the

end of the road.

After

Graham had thrown my gear into the limited confines of the Ford Anglia,

or whatever was his latest pride and joy, I would wriggle into the passenger

seat by ducking under the holdalls that protruded across the top of my

left shoulder through to the dashboard. Then, with bank sticks digging

into my neck, and drinks cans rolling in the foot well we would drive

off, yo-ho-ho-ing into the rain and darkness of a winter morning.

Stopping off to collect the baits from their hiding place was always a

bit of a pain and inconvenience. Ripping our clothes on the barbed wire

fence, with icy fingers we would search around at the water's edge for

the concealed cord. Sometimes when shining a torch into the water, we

would see the eels lurking in the vicinity of the basket, frustrated by

the plastic mesh. We would then have to tip the baits into the brewer's

bucket full of cold pit water, which could sometimes be crammed into the

boot, but which on many occasions would have to be wedged between my legs

for the whole journey.

At last the expedition was now under way. Careering along the unlit back

roads, we were soon belting down the long, straight road to Thorney. It

was always my duty to try to pick up something on the car radio, which

in every car I remember Graham having, was always bouncing around loose

on the parcel shelf in a nest of wires and connectors. Just about the

only station broadcasting at that hour was Radio Caroline, and to find

this I would have to turn the tuning knob painfully slowly, and listen

for the faint and erratic signal that would suddenly emerge apologetically

from between the ebbing and flowing of ignition interference and howls

of static. One of my most vivid recollections is that of listening out

for the tell-tale strains of Eric Clapton's Let It Grow, which almost

seemed to be on a constant tape loop.

On occasions we would have to make the detour to Dogsthorpe to pick up

Pete Harvey, the one time Nene carp record holder. Now nice guy that he

was, or even still is, Pete had absolutely no concept of urgency, and

while I was chomping at the bit to get to The Channel, Pete would just

bumble around and roll another fag, which meant that he would then need

to have another cup of tea.

Apart

from these frustrations, being the junior member of the party I would

be confined to the back seat of the car, barely visible under all the

stinking baggage. I really have no idea how on earth we managed to get

the three of us plus all the gear into one car, as they didn't even have

hatch backs in those days, and I now sometimes struggle to get all my

gear into a far bigger car for a simple all-nighter.

We would chug along the deserted straight up to Guyhirn, pass over the

river Nene into Norfolk, then set the controls for the heart of Kings

Lynn. Remembering to turn right at the outskirts (oops - reverse back

up the road), get into a wheelspin at The Metal Box Company and then steady

onto the home straight; although as straights go, this was an exceedingly

winding, twisted, bendy and slippery one. In the frosty twilight we would

skid sideways through slippery Elm, clatter through Outwell, then hopefully,

over and not into the Middle Level.

Before

long the high banks of the Tidal Ouse towered over the winding road, heralding

the run-up to the outskirts of the Holy Mecca itself, Downham Market Bridge.

Even in the near darkness, the wide expanse of the Great Ouse Relief Channel

reflected sufficient light for us to assess the conditions. Ideally, we

would cross the railway line at Downham Market as the very first fingers

of daylight were streaking the horizon, hoping to arrive at Denver Sluice

just in time to see the far bank gradually emerging from the gloom.

Parking

spaces were a bit limited; Ray Webb's caravan occupied most of the space

by the first gate and Neville's Del Boy three-wheeler was usually parked

by the far bank gate near "The Stones". First light on the Channel

was an incredible experience in those days and as we began the long walk

to the hotspot, there were always fish of all sizes rolling from one bank

to the other.

Everywhere

you looked, as far as the eye could see, there were dimples, swirls and

splashes as countless millions of fish broke the water surface; all this

at a time when the doom merchants were proclaiming that the zander had

eaten everything that ran, swam or wriggled. Heavily laden with tackle,

we would carry the bait bucket between us, trying to keep in step while

the thin wire handle bit into our fingers.

We first discovered our "hotspot" by just walking until we were

on the point of collapse. There was a long reed bed, through which fishing

was virtually impossible, followed by a clear stretch of about a hundred

yards that somehow looked a bit stark and uninteresting, but beyond that

the reed beds began again with just one or two gaps; just sufficient for

a couple of people to spread out the usual motley collection of rods.

Beyond that, the reeds continued almost uninterrupted to Downham Bridge.

We were later to find out that we had accidentally stumbled upon one of

the major Relief Channel hotspots, jealously guarded and fished by many

of the well-known predator anglers of that period.

Graham had two Bruce & Walker MkIV SU's apart from the other nineteen

rods he would put out, so was always able to use the more selective half

mackerel. I was limited to lighter baits on my eleven foot mongrel Avons,

so on one rod I usually launched a small deadbait on size 10 trebles as

far as I could cast it, and a larger livebait about twenty yards out on

the second. We were always plagued by strange indications on the long

distance rods. Sometimes we would get false bites due to the drag, but

sometimes the Fairy Liquid bottle top would go up and down a few times,

pull the line out of the elastic band on the rod butt, and then stop.

On one occasion I decided to hover over the rod and strike at the next

of these twitches. I made contact, and after a slow, ponderous fight,

reeled in a stone dead zander of about four pounds, hooked in the mouth!

I never was able to work that one out. On another occasion I had one of

about the same weight, although alive this time, that must have taken

the bait the instant it hit the surface in about fifteen feet of water.

I knew something was wrong when I kept trying to pull off some slack line

for the weighted bottle top, and it repeatedly insisted on pulling back.

The

Avon rods I had bought off Pete were a little bit on the soft side, and

the only way I had any chance of making contact to a take on the so-called

long chuck rod, was to tighten up as much as possible, then run with the

rod up the sloping bank behind me. This caused much amusement of course,

which only encouraged me to exaggerate even more. On one occasion I picked

the rod as if in response to a run, then ran right up to the top of the

steep bank and then down the other side. After missing this so-called

"run", I re-appeared feigning outrage and indignation at the

unfairness of it all.

One morning in one of the hot swims shortly after dawn, I was reeling

in a jack of about two or three pounds when something grabbed it a couple

of rod lengths out, then belted off along the rushes with it for several

yards before releasing its grip. The small pike was eventually retrieved

looking little the worse for its ordeal, but I was left quite shaken by

the sudden savagery of the events, as whatever had attacked it was obviously

very much larger than anything I had caught before. Graham had already

used most of the prime baits on his twenty-seven rods, but there was a

chub of about twelve ounces, which was considered a bit too large, but

which had been brought along for the ride.

I quickly bit through the line to remove the one and a half ounce bomb,

and decided that as I didn't have a float to support such a bait, I would

try to fish it freelined. Casting it was out of the question, so I nicked

the hooks through as delicately as possible, then with the bail arm open,

gave it a gentle under arm lob into the water. Its first response was

to try to swim back to shore, but with a bit of gentle pressure on the

line, I gradually coaxed it in the right direction. It was quite eerie

watching the line slowly trickle out, but then, before it had gone more

than a few yards, there was an almighty swirl on the surface, and the

line began to flow from the reel with rather more urgency.

Having

watched the more experienced pikers in action, I closed the bale arm,

waited for the line to tighten to the rod tip, then wound the reel until

the rod bent round into a curve. I briefly felt the resistance of a great

weight upon the end of the line, then all went slack. The poor, chewed

chub swam up to the surface and floundered around in circles. Within seconds

the waters opened up again, the luckless chub disappeared into a swirling

vortex. I repeated the approved procedure and tightened to the fish, only

to see the mortally wounded chub flapping feebly just under the surface.

As

I started to reel in, it had travelled just a couple of yards before it

happened yet again. There was a brief glimpse of an impossibly long flank,

and once again the line was running out between my fingers. The tension

and frustration was almost impossible to bear as I tried once again to

set the hooks with my underpowered rod. Perhaps my nerves were getting

the better of me, because this time I struck to no resistance whatsoever,

and I reeled my hooks back in on a slack line. Unbelievably, the chub

appeared just under the surface and gave a final flap before being dragged

to its doom for the final time.

By early afternoon I was usually starting to flag, and if it was warm

for the time of year I would sit back on my Efgeeco Pakaseat and fall

into semi-consciousness, while the wasps finished off the remains of the

deadbaits which by this time were starting to hum a bit. Occasionally

the cry would go out when someone contacted a zander right out of the

blue. This was usually on one of the end rods, and on many occasions run

would occur in sequence to baits fished further and further along the

line, until at the very end, past Graham's thirty fourth rod it would

eventually be the turn of one of mine...which I missed.

We always packed in before dark, as it was a long drive home and Graham

needed an hour or two to pack his rods away into their thirteen holdalls.

In theory, with the bait bucket now empty there should have been more

room in the car on the way back, but Peter H in his quilted thermal suit

occupied far more space than the same person without it. I could never

work out why he always used to keep it on, but it could have been that

once wedged into it he needed more energy to release himself than could

be mustered up after the long walk back to the car.

We

always stopped at the roadside shop at Salter's Lode before starting the

main part of the return journey. When I say "we" I really mean

"they", as it was physically impossible for me to get out without

someone else emptying all the tackle out of the car first.

Once underway, Harv would soon start to overheat, then unzip the front

of his suit to release all the unwanted aromas that had previously been

safely sealed inside. Combined with the acrid fumes of Players No.6, this

poisonous concoction would gradually turn my back seat prison into a portable

gas chamber, until half choking and with eyes streaming, I would be reduced

to begging for the last remaining dregs from a can of shandy, passed through

to me through the gaps between the holdalls.

When

I was eventually dropped outside my house I always felt obliged to recite

the traditional mantra, possibly from Crabtree, which I repeated every

week when getting out of the car: "And so we return; cold, tired

and hungry, yet strangely satisfied after yet another life enhancing day

at the waterside".

In return, Graham always felt obliged to maintain the tradition of throwing

my keepnet high up into the branches of a tree in the front garden before

setting off home.

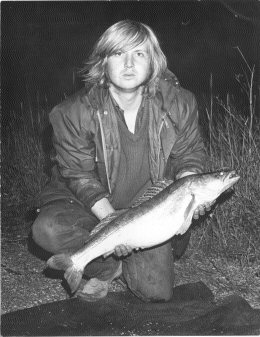

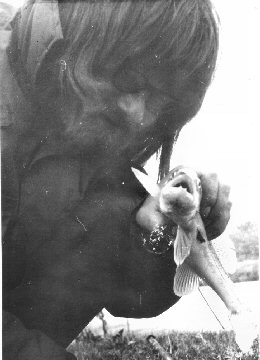

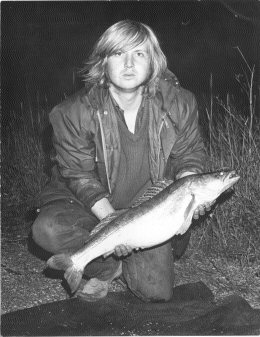

Close-up of my biggest Channel zander, which

stubbornly stuck at 9 lbs 15 ozs

HOME

|

The

original stocking was of just 97 zander

They

emerged from the water at night, laying waste to anything that moved

Vicious,

bicycle chain-wielding, punk thugs

Peterborough Specimen Group members

The

Electricity Cut - a festering cauldron

Dace,

mirror carp, chub, dace, eels, perch, roach, seahorses and sausages -

all highly sought-after as zander baits

High-tech

1970s bite indicators

Graham

owned a succession of special cars that were not generally available to

the public

The

manually-tuned radio bounced around on

the parcel shelf, secured only

by a tangle of wires and connectors

Let

It Grow seemed to be played on a loop

The

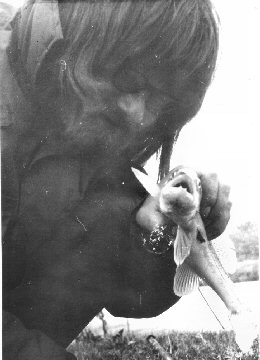

late Pete Harvey in favourite mode

The celebrated factory finish of a brand new Bruce & Walker,

from which Graham would remove the intermediate whippings, sand off, then paint a sludge-coloured matt khaki

The

late Ray Webb - he was an unusual man

The

Efgeeco Pakaseat, aka The Ejectaseat. Kept you awake by catapulting you into the nettles at random intervals during the night

Jeremy

Wade holds a Relief Channel zander

One of a large haul from Ten Mile Bank

One of a large haul from Ten Mile Bank

Graham

with a Relief Channel 12 pounder

Coming

to a river near you - a Trent zander

|

One of a large haul from Ten Mile Bank

One of a large haul from Ten Mile Bank